Balice Hertling project space

47 rue Ramboneau, Paris

« Now, therefore, putting these tiresome and absurd words quite out of our way, we may go on at our ease to examine the point in question- namely, the difference between the ordinary, proper, and true appearances of things to us; and the extraordinary, or false appearances, when we are under the influence of emotion, or contemplative fancy; false appearances, I say, as being entirely unconnected with any real power or character in the object, and only imputed to it by us. »

John Ruskin, 'Of The Pathetic Fallacy', Modern Painters (volume III, part 4, 1856)

« He's beautiful right ? Here you go, it's him ». Alex was describing to me an old school, rusty and half damaged gas container he got from Ksar Ghilane, an oasis in the South of Tunisia at the doors of the Grand Erg Oriental. He always talks about his objects as if they were friends. They are in a way : they've shared stories with him, they were on trips together, they are the testimonies of his ongoing career of smuggling newbie. Actually, this particular object kind of looks like him : ellongated, thin, and elegantly goofy. It is a sculpture already, a self-portrait maybe, not a ready-made.

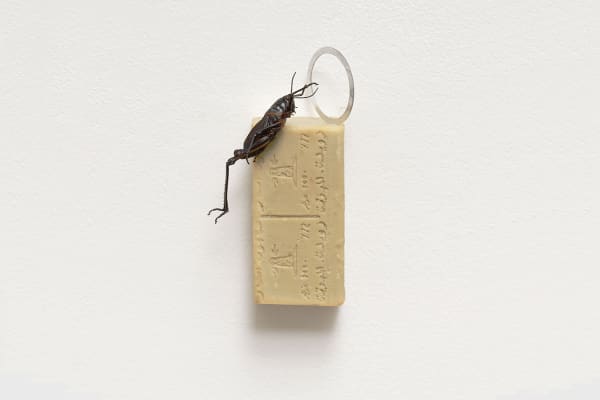

« My objects are tiny » he says. But he can speak for hours about each one of them, because they hold narratives, they point out to movements, traffics, and a certain idea of transiting through time and space. They hold the evidence of his attempt to get to the end of the Western world. « Am I there yet ? » is what's implied by the sand he swiped in the back of his car one night. But as the objects, the spaces are mere products of the gaze we project upon them. An exotic flower on an olive oil soap. Chianatown versus Moknine.

He's not interested in bringing forms that belong to other spaces and exoticize them into the white cube. He wants those forms to embody practices or postures, to be the physical incarnations of an oral tradition.

Alex plays with objects the way poets play with words : through associations, he creates mental images and each assemblage could be the substantial equivalent of a haiku.

Through improvisation and small acts of neglect, he elevates these objects, these companions, these pathetic fellows, to artworks that might be in conflict with the self-importance endemic to art and preservation. Occasionally, he throws in a surprising outlier that breaks any sense of a strict taxonomy : a fly or a dead cameleon would introduce a new gaze and highlight his obsessive, magpie- like eye for the mundane.

The pathetic fallacy is full on ; the shape of the objects has a tendency to disolve upon seeing them, but a few hours after the encounter, one can still remember the ephemeral matter they were whispering about.

- Myriam Ben Salah