Windowlicker

Balice Hertling project space

47 rue Ramponeau, Paris

an exhibition organized by Julie Beaufils, Ana Iwataki and Marion Vasseur Raluy

with works by Bogdan Cheta, Susan Cianciolo, Sean MacAlister and Paolo Thorsen-Nagel

To miniaturize is to make portable-the ideal form of possessing- things for a wanderer, or a refugee. Benjamin, of course, was both a wanderer, on the move, and a collector, weighed down by things; that is, passions. To miniaturize is to conceal. Benjamin was drawn to the extremely small as he was to whatever had to be deciphered: emblems, anagrams, handwriting. To miniatur- ize means to make useless. For what is so grotesquely reduced is, in a sense, liberated from its meaning-its tininess being the outstanding thing about it. It is both a whole (that is, complete) and a fragment (so tiny, the wrong scale). It becomes an object of disinterested contemplation or reverie.

- Susan Sontag, Under the Sign of Saturn

This act of miniaturization is one of making choices from the world to make manageable its enormity. It's at once the frag- mentation of the world and the existence of a little world. Intimacy, not breadth. To make one work of art, or to collect certain objects, or to organize an exhibition of certain artists and artworks allows a partial possession of what can never be completely possessed or assimilated or conquered. There is an easing of the painful pangs of desire, of lack, and the need for more. A salve, not a cure.

Lèche-vitrine, the French for window shopping, literally translated as "window licking", suggests the pleasure of possession via the act of looking at an ensemble of objects, forming a little universe of their own under glass. In an act of surveillance, Bogdan Cheta worked at a desk facing the vitrine in what served as the office in Balice Hertling Bellville. Taking on the double role of spectator-spectacle, subject-object, he confined himself to both the gallery's walls and his view onto the rue Ramponeau. A strange triangulation unfolded, a line of vision bouncing from Cheta and the gallery, to a surveillance camera pointing towards him, to a neighbor across the street on his balcony, and back again. This drama is recounted for us in a resulting text piece, and visitors are invited to take the place of the artist and the gallerist at the desk, to confront their own acts of voyeurism. Cheta further interacted with the gallery by tracing a horizon line along its walls at the height of his outstretched arm.

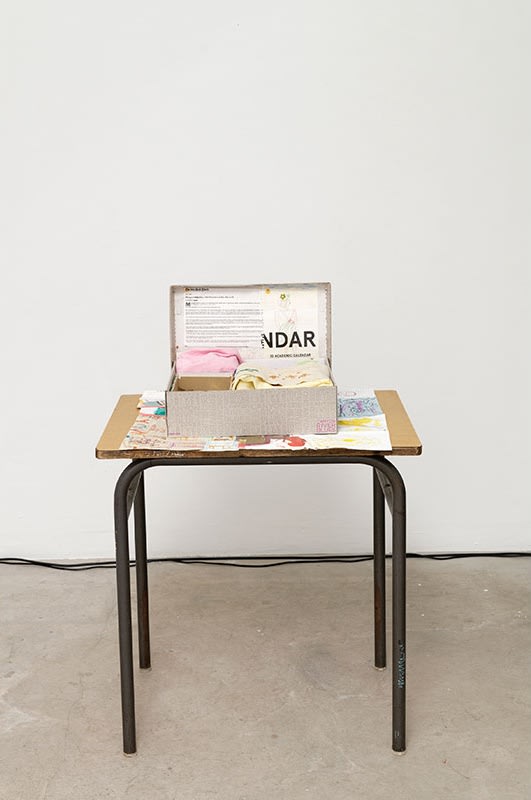

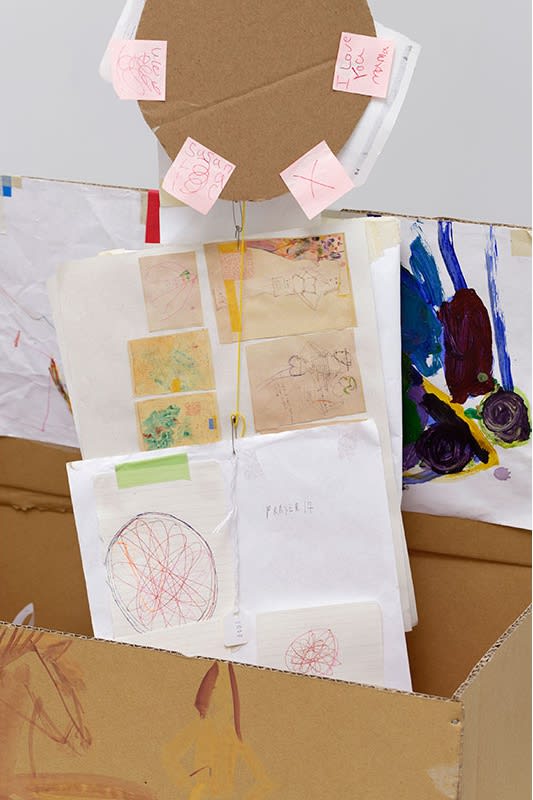

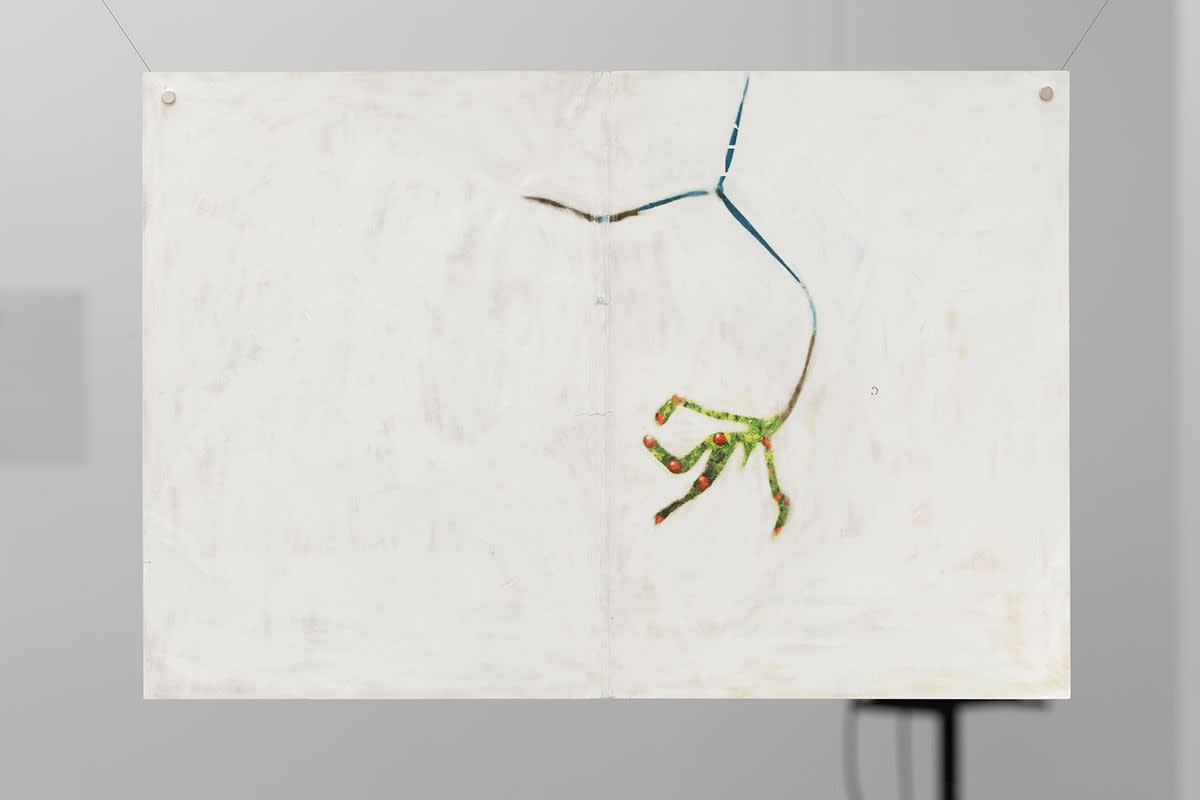

His explorations offer a distant echo to Susan Cianciolo's "kits". Installed on quilts, tapestries, or other small works by the artist, and here presented on simple school desks, these kits are composed of miniature paintings, annotated photographs, notes, post-its, diaries, bits of fabric, paper, and other "painfully personal" remnants of the artist's life and career. These portable works, touching in their intimate size and content, are at once small universes, time capsules, archives, reliquaries, tool kits for transformation. In the 90s, Susan Cianciolo came to prominence as a fashion designer, particularly for her critically-acclaimed collection RUN. She quickly became interested in the context of creation and in 2001, she transformed the Chelsea Gallery into a teahouse, fashion boutique, and exhibition space. She continues today to work at the border of fashion and contemporary art.

Paolo Thorsen-Nagel's sound work permeates and travels around the gallery in such a way that suggests the viewer likewise become a flâneur within the space. His piece-suggestive of many auditory diasporas-insists that there is not one ideal van- tage point for listening, that one position should not be privileged over any other, and that instead one might listen to the room playing itself. We hear sounds from his metro ride to the airport in Athens, recorded by a sound coil that picks up a limited range of electric frequencies. A capturing of the world, yes, but in a decidedly constrained manner: miniaturization via electromagnetic